In 1858, 97 years before Rosa Parks would not give up her seat on a bus in Montgomery, Alabama, Unitarian author and poet, Frances Ellen Watkins Harper did the same on a Philadelphia horse-drawn streetcar. Her actions, and the later humorous retelling of the story, in The Liberator, helped many realize the idiocy of racism and the capacity to face it with dignity and courage. In honor of Harper, Black History Month, and our Soul Matters theme of “Embodying Resilience,” the following poetic interpretation of her actions is offered as a meditation this month.

“The Courage to Stay Seated” by Rev. Aaron Payson (AI Assisted)

Take a breath, and let your body settle into this moment.

Let your feet find the ground beneath you—solid, steady, holding your weight without question or hesitation.

Now imagine another set of feet, another body, another morning.

It is 1858.

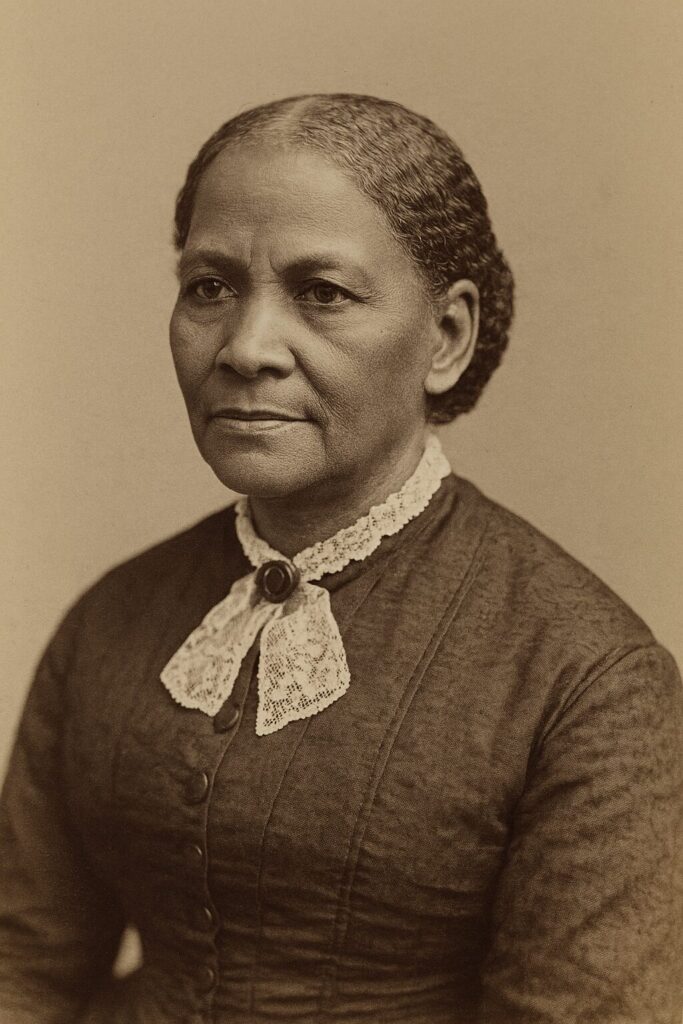

A Black woman—Frances Ellen Watkins Harper, poet, abolitionist, teacher, fierce defender of human dignity—steps onto a Philadelphia streetcar.

She is told she must leave.

She is told she does not belong.

She is told that the space her body occupies is a space reserved for someone else.

And she refuses. She stays seated. Not with anger, though she had every right to it.

Not with violence, though violence had been done to her people for generations.

She stays seated with a calm, unshakable clarity:

I am a human being. I am here. I will not be moved.

In her letter “Our Greatest Want,” Harper tells this story not to center the humiliation she endured, but to illuminate the moral courage she believed the nation lacked.

She writes of a deeper need—not simply for laws or reforms, but for a transformation of character.

A moral awakening.

A willingness to see one another as kin.

“Our greatest want,” she insisted, “is not wealth, but men and women who will stand for right and truth.”

Let that settle in your chest for a moment.

Let it echo.

What does it mean, today, to stay seated in the face of injustice?

What does it mean to refuse the lie that some people belong more than others?

What does it mean to cultivate the moral courage Harper called forth—courage rooted not in domination, but in dignity?

Breathe into those questions.

Because the streetcar has changed its shape, but it has not disappeared.

It shows up in who is followed in a store.

In who is pulled over.

In who is believed.

In who is welcomed.

In who is detained and deported.

In who is safe.

In who loses their life in the process.

It shows up in the quiet calculations of whose comfort matters most.

In the subtle ways we are asked to move aside, to shrink, to make room for someone else’s sense of entitlement.

And it shows up in the choices we make—every day

About whether we will speak,

Whether we will intervene,

Whether we will stand or sit or stay.

Harper’s story is more a story of presence than resistance.

It is a story of a woman who knew her worth so deeply that no conductor’s command could shake it.

So as we breathe together this morning, may we draw on her strength.

May we feel her clarity settle into our bones.

May we remember that courage is not always loud.

Sometimes it is simply the refusal to surrender our humanity—or anyone else’s.

Take another breath.

And as you exhale, imagine sending a blessing backward in time to Frances Ellen Watkins Harper—

for her steadfastness,

for her vision,

for her insistence that the moral arc, that our ancestor Theodore Parker described, does not bend on its own.

And now imagine sending a blessing forward—

to the world we are still building,

to the streetcars we still ride,

to the moments when we, too, are asked to choose between comfort and conscience.

May we choose well.

May we choose boldly.

May we choose, again and again, to stay seated in the truth of our shared humanity.

Amen & Blessed Be.